Midwifing Double Ghost Dactyls

Notes from the Frontlines of HOW TO SCAN A POEM: A POETRY WITCH WORKBOOK

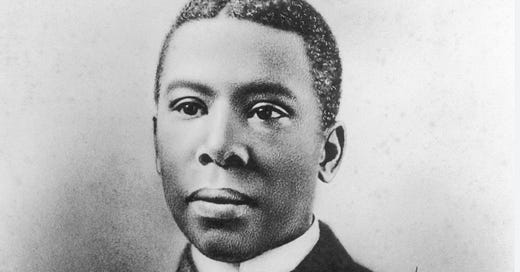

Paul Laurence Dunbar—master of the double ghost dactyl

Years ago when I was deep in writing the meter sections of A Poet’s Craft/A Poet’s Ear, I discovered the advantages to being obsessed with a field of thought—metrical diversity and its various prosodic incarnations—that apparently no other poet writing in English gives a syllable about. There are disadvantages too, don’t get me wrong. There have been lonely, scary, frustrating moments. But I’ve been called to this work so powerfully—in will, mind, body, heart, and spirit—that I’ve literally had no choice. And as if to validate my Poetry Witchery path, ultimately the universe always seems to comes through with the support to keep me going. And with amazing friends, colleagues, and students. And with freedom and independence. And with creative and intellectual joys beyond measure. The advantages have been, truly, priceless:

Advantage 1. You can take your time. When nobody cares what you’re doing, there’s no rush to get something into print quickly to counter someone else’s misconceptions or correct a narrative. It took me almost twenty years to write A Poet’s Craft/A Poet’s Ear, and in the decade since they were published, I’ve continued to take all the time I’ve needed to tweak my ideas exactly to my liking.

Advantage 2. You can make new claims and invent new vocabulary if needed. This is a heady privilege, and of course easy to abuse. But when done in a spirit of genuine service, it is truly satisfying. While discussing noniambic variations for the “Metrical Palette” chapter of A Poet’s Craft/A Poet’s Ear, I could find no guidelines for variations in noniambic meters (gudielines for iambic meters were established by Wimsatt and Beardsley in 1959). With the help of years’ worth of students, I developed and articulated my own guidelines, creating appropriate terminology where needed: “running start” for extra cups at the beginning of a trochaic line, “footless” (by analogy with “headless” in rising meter) to describe a line in falling meter missing final unstressed syllables. No prosody police pulled me over, and it seems that my conceptualization of the guidelines has been helpful to many readers.

Advantage 3. You can improve on existing terminology. This is loads of fun, especially for a poet, of course. When I could no longer stand saying the boring terms “accent” and “secondary accent,” let alone the miserable phrase “unstressed syllable,” forty times each during a single class, I set out to find simple, concrete nouns to replace them and settled on “wand,” “half-wand,” and “cup.” My students loved it, and nobody in the prosody world even noticed. And again, I could take my time! It took another six years before I finally hit on the perfect one-syllable noun to replace the horrible term “foot-boundary.” The terms I now use for accented syllable, secondary accent, unaccented syllable, and foot-boundary are wand, half-wand, cup, and edge. Feel free to use them—they’re all yours!

Advantage 4. may sound strange, but it’s true: you end up in a position to learn more deeply from your readers and students than those in more populated fields of knowledge probably ever will. Due to the lack of other resources offering the type of knowledge you are developing, those interested in your ideas will likely stick with you longer, learn your vocabulary, and study more deeply what you have to share. Eventually they will be in a position to challenge your assumptions and hold you to task harder than if they had been absorbing a wider field of similar yet conflicting ideas. Of course, it’s up to you whether you choose to learn from those who have learned from you—but if you do, your ideas will be stronger for having been tested. I’ve noticed this pattern in the work of other freethinking feminists shut out of the official academy—including the anthropologist Heide Goëttner-Abendroth and the economist Geneveieve Vaughan—both of whose ideas have been refined by the questions and concerns of an intensely connected group over the years.

Advantage 5. It is incredibly fun—not only for you, but also for those who are helping you! Case in point:

The amazing conversations I’ve been having the last few days with Autumn Newman, the Scansion Assistant for the book I’m finishing up, How to Scan a Poem: A Poetry Witch Workbook. When Politics & Prose Bookshop invited me to teach an online course in scansion, and it turned out there were no suitable poetry anthologies in print, I seized on the chance to create the workbook I’ve thought of creating for years. I will unveil it next week, as a text for the course.

Autumn is a talented poet who first learned scansion from me when I was directing the Stonecoast MFA Program. Since then, she has taken numerous classes with me, including repeated sessions of the intensive Formal Feeling metrical poetry workshop that I taught to a small group of advanced women and gender-nonconforming poets for several years. When I met Autumn she had the word POET tatooed on her chest—and today that word is scanned! Like me, she is a survivor of patriarchy who made it through with the help of poetry, scansion, and metrical diversity (my term for a commitment to writing in multiple meters, not only iambics—I normally teach 5 or 6 meters). I feel that for both of us, scansion is a magical, sacred art—not only deeply meditative, but potentially deeply transformative, connecting us directly to the ancient oral traditions of shamanic journeying and healing that have followed the path of meter’s power the world over since the dawn of the human species.

When Autumn and I talk scansion, all the poetry Goddesses must be dancing ecstatic circle dances somewhere in Muse-land, because we are truly practicing Deep Scansion: we listen to the meaning level and the sound level of each poem at every point, both within the foot we are scanning and within the poem as a whole, bringing meter and meaning into full communication with each other until we arrive at the optimal scansion for each syllable on the levels of will, mind, body, heart, and spirit. *

The last few mornings, when Autumn and I spent hours on the phone going over her scansions of the 35 or so poems in the workbook together, were an amazingly heady experience—truly one of the most remarkable experiences of my intellectual life. We found ourselves inventing new terminologies for specific metrical variations, to more efficiently discuss our scansions. “Double ghost dactyl” is my favorite of these, the one I think should be the name of a punk band. It refers to a dactylic foot at the :end of a line that is missing the final two cups, as in lines 2 and 4 of the final stanza of Paul Laurence Dunbar’s “The Paradox”:

/ u u | / u u | / u (u)

Come to me, brother, when weary,

/ u \ | / u \ | / (u u)

Come when thy lonely heart swells;

/ u u | / u u | / /

I’ll guide thy footsteps and lead thee

/ u u | / \ u | / (u u)

Down where the Dream Woman dwells.

Other fun terminology we came up with in the press of these heady hours of high-level scanning are “half-cretic” — a cretic foot with a half-wand in place of the final wand, as in second foot of line 2 of this stanza above—and half-iamb and half-trochee—feet that replace their cups with half-wands.

Also during our conversations, I was finally able to complete the list of Guiding Pricniples for Scansion that I’ve been developing over the past decades of teaching. These will be available in How to Scan a Poem in a week or two—I have no choice—going to finish polishing up the book right now because the classs starts in less than two weeks! —and I will probably discuss them at more length here in ths substack also.

*Knowing it may be hard to imagine such a discussion, Autumn and I recorded our second conversation, and I will be posting it soon HERE (Link will appear here, so watch this space) to give you a sense of it.]