Meter, Gender, Control: Yeats' Iambic Struggle in "When You Are Old and Gray" (conclusion)

(A Scansion Deep Dive)

Some information on the scansion symbols used is available under the Scansion heading. To learn more about meter and scansion, check out the resources in the Cauldron.

Here’s the promised Part 2 of my Deep Scansion reading of Yeats’ “When You Are Old and Gray.”

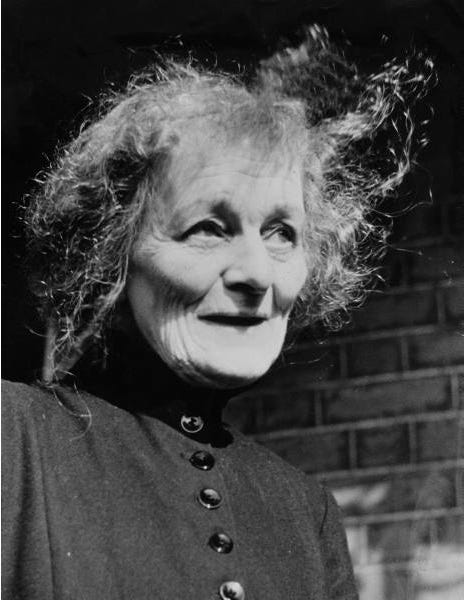

Near the end of Part 1, I had recommended that you “enjoy [the poem] as innocently as you can, just as my mother and sisters and I used to do in our kitchen, because what you read in part 2 of my analysis may affect your relationship with it forever.”

Well! OK then! My own philosophy of scansion and other forms of poem-receiving is that the more fully we allow ourselves to understand—even if it means having to jettison cherished conceptions—the more authentically useful will be the new pathways opening before us. In poetry as in life, this basic trust hasn’t failed me yet.

And if you’ve read this far you may well agree, at least as far as scansion is concerned. So let’s smite some furrows and push off into the sounding granularity of this conflicted poem’s metrical mysteries, complete with all their wider cultural resonances (In the interest of focused exploration, I’m laying aside my own personal Yeats tales. . . but only till some other day!).

(The poem is written in 3 quatrains; sometimes Substack refuses to show the stanza breaks.)

WHEN YOU ARE OLD

u / | u / | u / | u / | u /

When you are old and gray and full of sleep,

u / | u / | u / | / \ | u /

And nodding by the fire, take down this book,

u / | u / | u / | u u | / /

And slowly read, and dream of the soft look

u / | / / | u u | \ / | u /

Your eyes had once, and of their shadows deep;

u / | u / | u / | u u | / /

How many loved your moments of glad grace,

u / | u / | u u | / / | u /

And loved your beauty with love false or true,

u / | / / | u / | u / | u /

But one man loved the pilgrim soul in you,

u / | u / | u u | u / | u /

And loved the sorrows of your changing face;

u / | u / | u / | u / | u /

And bending down beside the glowing bars,

/ u | u / | u / | u / | / /

Murmur, a little sadly, how Love fled

u / | u / | u / | u / | u /

And paced upon the mountains overhead

u / | u / | u / | u / | u /

And hid his face amid a crowd of stars.

On the metrical level, I read this poem as the 26-year-old poet’s struggle to reassert—and serve—- the reassuring rationality of inherited iambic privilege, in the face of the deeply-rooted threat of a more chaotic and female trochaic energy. Line 1 is a completely regular iambic pentameter made entirely of monosyllables: “when you are old and gray and full of sleep.” A line composed of monosyllables, paradoxically, sets the metrical scene most decisively; monosyllabic are so malleable that the meter of such a line feels most random, most arbitrary—and hence most forcefully imposed. As we hear or read the poem’s opening, a subterranean part of us registers the fact that these words could be almost perfectly rearranged into a trochaic line, something like: “Gray and old are you and full of sleep when,” or into a line that could sound quite dactylic: “When you are gray and old, and full of sleep.” The poem’s existing opening, then, is all the more forcefully iambic not in spite of, but because of this monosyllabic flexibility. Other metrical possibilities are repressed more thoroughly than they would be by a line incorporating polysyllables, e.g. “When you are ancient, dozing fast asleep.”

In this way, the poem’s opening clearly and forcefully establishes an iambic pentameter “metrical contract” (to use my teacher John Hollander’s useful term for the rhythmical understanding between poet and reader). To the extent that iambic pentameter is, and was in Yeats’ time, by far the most conventional of meters, Yeats here offers us a formulaic poetic opening, the metrical equivalent of the words “once upon a time.” Like all instances of “once upon a time,” in the very act of lulling us, it promises us that the formula will soon be broken—and that we will be treated to conflict, in this case metrical conflict. Sure enough, by the third syllable of the second line, we know we’re in for a phenomenal metrical ride, a complex prosodic experience.

The word “nodding,” the first word in the poem of more than one syllable, is so intensely trochaic that, especially followed by the soft syllable “by,” it establishes a firm counter-rhythm to the basic iambic meter. The trochee wakes us up,

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Annie Finch's Five Directions to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.